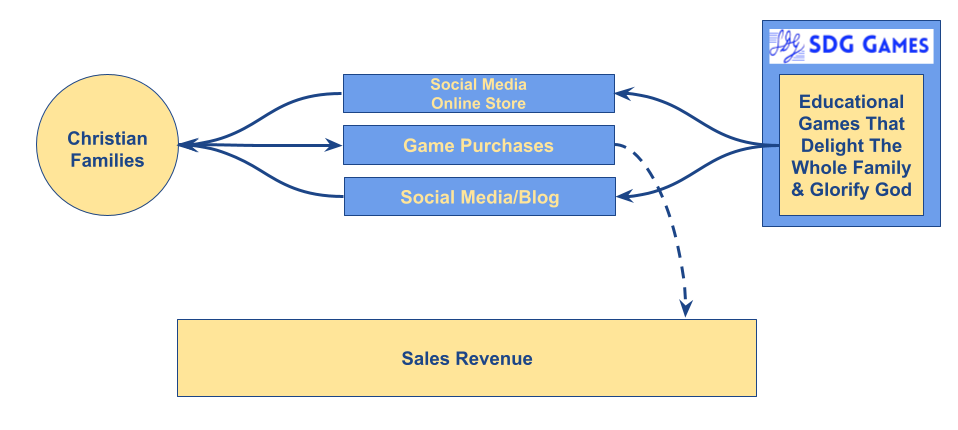

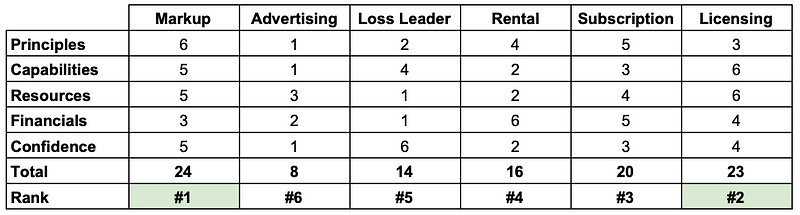

About a month ago, I wrote about the Revenue Model for SDG Games. At that time, we identified that there were two models that were most attractive, one that we would pursue near-term (Markup) and one that we would like to pursue longer-term (Licensing). As we get closer to building out the full operating model for the business, I think it’s important that we dive another level deeper into the Markup model.

Like many others, the nature of the board game industry has been radically transformed over the past 20 years.

People have been playing board games since well before the time of Christ. An early form of backgammon was popular across the Roman Empire. The game of Go was invented in China around 400 BC and a form of the game Snakes and Ladders was invented in India around 200 BC. Versions of games similar to Chess are found in Scandinavia, India, and Persia around 500–600 AD. Naturally, prior to the industrial revolution, all of these games were handmade, one by one.¹

The industrial revolution, especially advances in paper making and the printing of products, created the board game industry. As work and home life became distinct, the market for leisure activities, including gaming, also grew. In the early 1800s, most boardgames focused on teaching Christian principles and morals, with best-sellers including The Mansion of Happiness and The Checkerboard Game of Life². By the end of the century, the focus of many games had shifted to materialism and accumulating wealth.

Throughout the modern history of the board game industry, small innovators have created games that captured the world’s attention. Examples include Milton Bradley (The Game of Life) in the mid-1800s, McLoughlin Brothers (District Messenger Boy) in the late-1800s, Parker Brothers (Monopoly, Risk) in the early 1900s, and Selchow and Righter (Scrabble) in the mid 1900s. However, in the 1980s, Hasbro began consolidating the board game industry, buying all the companies previously listed in this paragraph. Hasbro now has an estimated 80% share of the board game market³.

During that same period, the retail industry radically changed, with the growth of big box retailers including Toys-R-Us and WalMart driving many small, independent toy and game stores out of business. Independent game publishers have had a much harder time competing with Hasbro for limited shelf space in the games sections of the big box retailers, tightening Hasbro’s lock on the industry, and making it harder for gamers and their families to discover new titles.

The Internet has started to change that, impacting discovery, manufacturing, and marketing. The BoardGameGeek website was launched in 2000 and today includes a database of over 120,000 board games and a marketplace for gamers to buy and sell board games. The Internet also made it much easier for game developers to find and connect with low cost manufacturers around the world (most notably in China). The Internet also connected creators to on-demand production capabilities including high quality printers and 3D printing. The Kickstarter website and business was launched in 2009 as a platform to help creators find backers for their creative projects.

The end result is that today most new games take one of three paths to market:

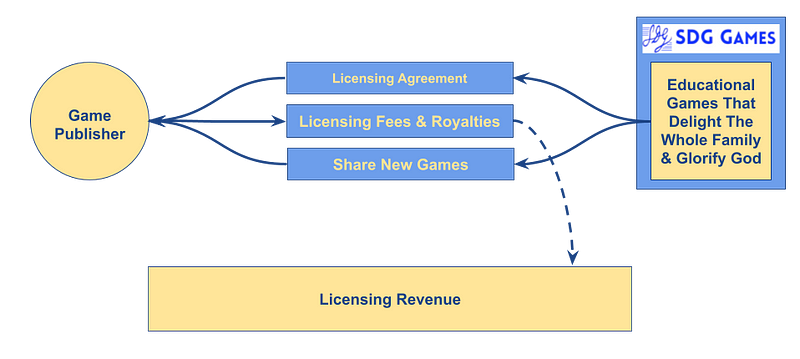

Licensing: A game designer can license their game to an established game publisher which has existing manufacturing and distribution capabilities. For example, some retailers will only consider new games from publishers with whom they already have a relationship.

Self-Publishing/Crowdfunding: A game designer can decide to try to go it on their own. They can run a Kickstarter campaign to get enough pre-orders to fund an initial manufacturing run, find a Chinese manufacturer to produce the game at low cost, ship and warehouse the produced games, and convince distributors and retailers to carry the game.

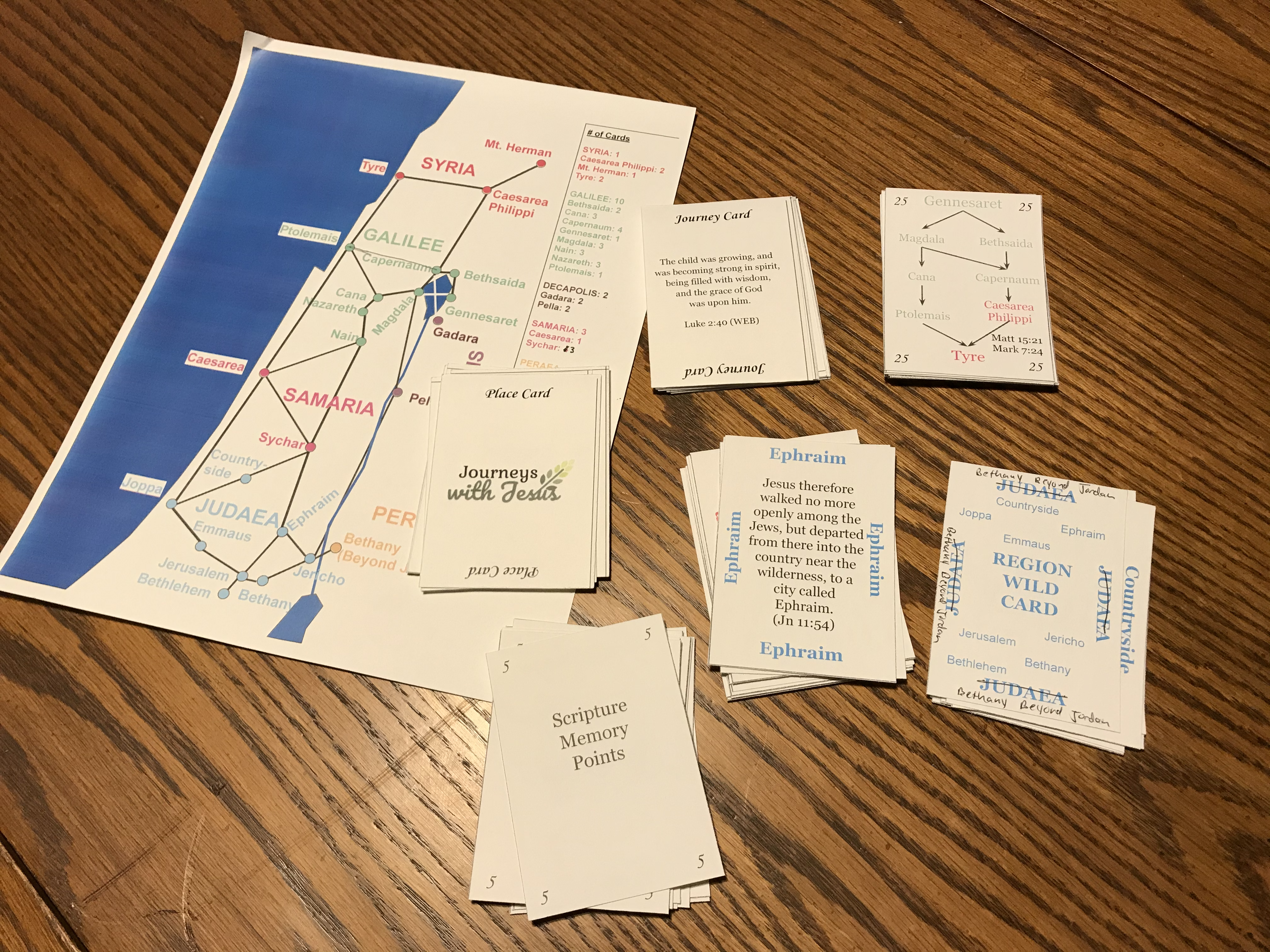

Self-Publishing/Print-On-Demand: A game designer can take a lower risk path to going it alone by using a Print-On-Demand service like The Game Crafter (TGC). TGC provides a storefront through which customers can buy your game. No inventory is maintained. When an order is received, it goes into the production queue. It get’s printed, packed, and shipped directly from TGC to the customer.

Of these three approaches, the Crowdfunding path requires the most work and involves the most risk, but results in the highest profits for each game sold. However, you need to make sure you sell enough to cover the cost of all the games you manufacture.

Licensing requires the least work, but you lose all control over your game. You don’t know how it will be marketed (or even if it will be). One game publisher shared that they typically pay 7–10% royalties on Gross Sales Revenue (the amount they are paid by a distributor, which is often 40% of the retail price). If your game is marketing by a major publisher, it likely will have much higher total unit sales than if you go it alone.

The Print-On-Demand (POD) approach requires some up-front work to create the attractive digital files uploaded to the printer, and some level of self-marketing, but very little work managing the manufacturing, sales, and distribution. However, this approach likely results in the lowest sales volumes and lowest profits. The cost of manufacturing with POD is probably 4–5x that of having the game manufactured in China. That means that the cost of production makes distribution through traditional brick-and-mortar and online retail channels economically unviable.

The SDG Games Distribution Strategy

Given that SDG is a one-person organization across consulting/coaching and game design, for now the Crowdfunding approach is not realistic. That greatly simplifies our distribution strategy.

Optimally, one of our games will be attractive to a publisher. For that to be true, we likely will have to be successful in our initial independent marketing efforts. For now, we will focus on the POD model using The Game Crafter. We will market via social media, our website, and our e-mail newsletter. We will sell through The Game Crafter store, and sales will be fulfilled by The Game Crafter.

If/when we have enough success through POD with any of our games to prove market demand, we can begin approaching existing publishers about licensing. If we are successful licensing one or more games, then the publisher will take full responsibility for all aspects of game production and distribution.

Most startups will need a much more sophisticated distribution strategy, dealing with acquisition marketing, retention marketing, distribution, sales, and customer support. Let me know if I can be of any assistance in helping you develop your distribution strategy!

Sources:

¹The information on the ancient history of board games largely comes from “The Complete History of Board Games” by Byron at Geek Gear Galore https://geekgeargalore.com/boardgames/history-of-board-games/

²Some of the information on games in the industrial revolution comes from “Board Game History: The Birth of the Modern Board Game” by Shannon Appelcline at Mechanics and Meeples http://www.mechanics-and-meeples.com/2013/01/14/board-game-history-the-birth-of-the-modern-board-game/

³Some of the information on industry consolidation comes from “Hasbro: The Creature that Ate the (Gaming) World” by Shannon Appelcline at Mechanics and Meeples http://www.mechanics-and-meeples.com/2006/06/08/the-creature-that-ate-the-gaming-world/